Something kind of crazy is happening on Broadway right now: Go figs, the first two major new musicals of the season, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson and The Scottsboro Boys, are both really good.

I know.

What even in hell is going on here?

Besides that, these shows do actually have something in common; they both examine American history with a satiric eye. But while Bloody Bloody looks at the past through a contemporary lens, The Scottsboro Boys is in the style and entertainment of the era in which the events took place. That is to say, it’s presented as a minstrel show.

And how do the creators of this show get away with staging a minstrel show in 2010 without offending everyone on earth? They use it to tell a harrowing story of racial injustice—the wrongful conviction of 9 black men for the rape of a white woman in Alabama in 1931.

The show’s humor is acerbic—indeed, the audience is asked to laugh within some horrific contexts—but the moral message is clear. Here are some other things in The Scottsboro Boys to take note of

1. The (relative and debatable) genius of Susan Stroman: So, I’ll just put it out there: I’m not a major fan. The Producers was a sexy-as-a-brick letdown, and Stroman’s other work has landed on so many Must Avoid lists that I actually listened. But I liked the particularly Stroman-y qualities of The Scottsboro Boys—the razzmatazz choreography, the mugging to the crowd, the “let’s-put-on-a-show, boys!” verve of the thing. All of that works within the minstral show construct. Which of course made me wonder if Stroman had found a niche that really works for her. Bummer that it’s in a totally antiquated format.

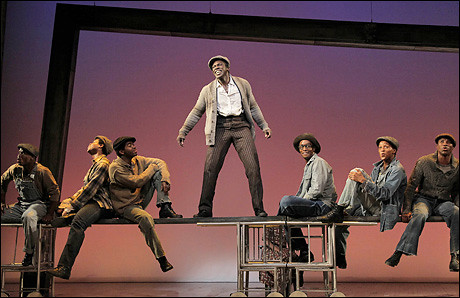

2. The 2011 Tony nominess for Best Actor in a Musical: Joshua Henry left such an impression in American Idiot in such a tiny blip of a role. As the single standout star of The Scottsboro Boys, he commands the stage as Haywood Patterson, one of the accused men. Patterson, in real life and in the show, goes on to chronicle the events in a book, and as such, he’s the show’s emotional center. Breaking through the minstral show’s bawdy, joke-y veneer, Henry delivers the show’s most emotional moments with real, big-singing power.

3. The benefits of a really good ensemble cast: Everyone in The Scotsboro Boys does everything. They sing. They dance. They play the comedy and the drama with equal panache, and with so much energy. Their formidable talent is an important ingredient—it makes a very tough, sad story very easy on the eyes and ears.

4. The viability of super old-time-y entertainment, in two ways: Yes, the minstral show is a totally old (that is to say, extinct) form of entertainment that takes on new life in The Scottsboro Boys. But really, this show has more in common with the Kander and Ebb musicals of the 60s and 70s than with minstrelry. Yes, there is the cakewalk and Mr. Tambo, but there’s also the hero-identifying opening number, the big moment-of-reckoning character ballad, the tap number. There is nary an electric guitar in earshot and the youth-mongering angst of a Spring Awakening is nowhere to be found. In a lot of ways, this is super-traditional, classic musical theater. It dodges the pitfalls of that form, and feels fresh only because the subject matter hits so hard, and because reviving the minstral show feels so audacious. But really, at its heart, this isn’t a subversion of the minstral form. It’s a clever subversion of the classic musical form.

5. The mess in your head: The Scottsboro Boys challenges its audience to think big about its themes of inequality, justice, and racism, and there’s no attempt at a happy ending. A show like Chicago, for example, deftly implicates its audience in the end, but the message here packs a lot more punch: In fact, the show makes a startling point: The course of history has been tragic. It’s up to you, gentle theatergoer, to fix it in the future.

Photo: Paul Kolnik

{ 0 comments… add one }