Right now the good folks over at the Belasco are probably up to their eyeballs in glowing reviews. As they should be. Richard III and Twelfth Night, imported by Shakespeare’s Globe in London — playing in rep and staged as they would have been in Shakespeare’s time (that means all male casts) — are absolutely fucking marvelous. Revelatory. Enlightening. Mark Rylance will change the way you think of Richard the III. Or Olivia, for that matter. Actually… he’ll change the way you think about everything if you watch closely enough.

Which is the thing I need to tell you about.

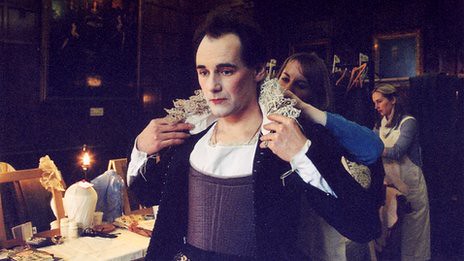

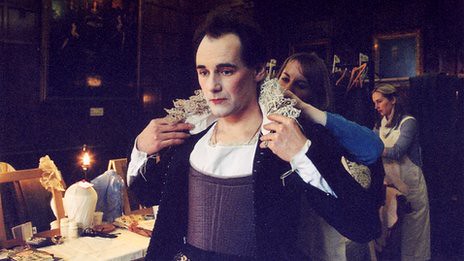

Before each show at The Belasco, the cast gather on stage to don their costumes, and where necessary, makeup. There is no curtain. The audience, or at least, anyone smart enough to arrive early, is privy to a scene normally hidden offstage, behind closed doors. Dressers and makeup artists abound as the men slip into period garb and chat, or pace, or drum on the tables along with the period music the band is playing. As they do their getting-ready-to-illuminate Shakespeare thing.

I could probably opine for hours on how amazing it is that not only does this experience not hinder the audience’s ability to suspend disbelief but it actually manages to enhance our connection with the material. As if our complicity in the act makes us more invested in the journey.

But what I want to tell you is more specific. It’s about watching Mark Rylance before Twelfth Night as he puts on his Olivia costume and, layer by layer, sheds his entire self to become a woman. It will wreck your head.

Having seen Richard III in the afternoon, I knew that the cast would be getting into costume on stage before the show, and that evening I returned to the Belasco early so I could catch as much of the Twelfth Night costume change as possible. It was maybe the best decision I’ve made in my entire theater-going life. The costume change before Richard III was interesting. But, to be frank, Rylance is the guy to watch on that stage, and in Richard III he goes through a much less pronounced transformation. Not only is his costume less complex, but as Richard he remains a man, and a showman, at that. There is something that feels inherently Rylance-ian about Richard.

But Olivia — when he becomes Olivia. Oh. My god.

As Mark dons each layer of his costume — and lord, are there layers in those women’s costumes — some piece of the Mark Rylance you’ve seen and known disappears. The man changes everything about himself that can be changed. The way he holds his face. His posture. The way his wrists move. The way he walks. THE WAY HE BREATHES. I shit you not.

And watching each small change, from the way he aggressively flaps his hands as though he’s trying to break something in his wrists to change how they feel and work, to the way he inhales and exhales, so that his whole person feels different just there before your eyes, is insane. It wrecks your head. Because you are SEEING IT HAPPEN. Like. You know what he’s doing. And still, you cannot believe your eyes. Or even remember what Mark Rylance was like before, when he was Mark, or Richard III, or anyone but Olivia, the woman right there before you.

Of course, it takes more than a dress, or a posture, to be a woman. There is some spiritual and emotional vein of existence that Rylance taps into, and which you can see the beginnings of right there on stage. I wish I could explain that part to you. That transference of something otherworldly into his being. How Rylance’s understanding of Olivia is obviously so much deeper than gender or performance.

But that’s the privilege of being there. Of seeing this. The greater understanding of his work, and maybe of humanity, too. I mean. To be totally ineloquent here, this shit fucking blew my mind into a thousand pieces and heightened my experience of Twelfth Night and made me want to see it again and again and again. I mean. It was so good I haven’t even mentioned how much more in love with Samuel Barnett I am (seriously, can we cuddle and drink tea and talk about books forever?), which, with me, is really, really saying something.

So just… go. The plays will change the way you think about Shakespeare. And get there early. Because the show before the show will change the way you think about theater and basically everything else, ever.

Photo: BBC